Part 1: The Cost of Urbanization

Is the prospect of towering high-rises so paramount as to obliterate the very green heritage that gives us life and binds us together as a nation?

How are the ’soft’ questions being addressed amid the growing ‘hard’ industry in Pakistan? At what cost is urbanization finding its roots?

As concerned Pakistani citizens, we understand the grave need for ‘green’ preservation, an idea that is seldom currently addressed by the necessary authorities. In a time where deforestation concerns are supplanted by political matters deemed more ‘pertinent,’ the urgency to restore and further expand former traces of green activism has been replaced by a barren void.

Pakistan Chowk Community Centre in collaboration with the National Heritage Association of Karachi, has launched Pakistan’s first digital green preservation initiative, the “Banyan Tree Project.” The Banyan Tree Project, a tree rehabilitation and conservation initiative, aims to bring together activists, entrepreneurs, and innovative-thinkers to raise awareness, and put an end to the negative repercussions triggered by the mismanagement of nutrient-rich land.

Part 2: Why Banyan Trees?

Banyan Trees, due to their extensive cultural and historical background, are ripe with tales of our collective past as a nation. The etymology of the species itself is native to the Indian subcontinent; derived from the Gujrati term for merchant “bania,” Banyan Trees trace back to the rule of the British Raj, when traders often sold their products under the shade of Banyans’ ever-laterally extending crowns. In addition to serving as a distinguishing factor for colonial architecture, Banyan Trees thrive under the high moisture, warm-climate conditions that are typical of South Asia, and are good candidates for climate resilience in the face of carbon emissions. Due to their dual roles as ecological linchpins sustaining diverse biodiversity and their capacity to procreate when branches develop new roots by simply touching the ground, the mystical quality of Banyan Trees has often been described in ancient texts and scriptures as a symbol for longevity and the divine.

Merchants continuing the age old tradition of selling their wares under the shade of Banyan trees.

Part 3: Measuring Carbon Sequestration (carbon absorption by trees)

In addition to their contribution to our cultural heritage, Banyan trees permanently absorb between 50-75% of our carbon emissions. According to data from 8billiontrees, 1.3 tons of carbon emission are captured by the average Banyan tree over the course of its lifetime. Pakistan’s average carbon footprint, when measured per capita, is estimated at 1.04 tons of CO2 per capita annually (EuroStats). With the average life expectancy in Pakistan approximated at 67.43 years according to data provided by the World Bank in 2020, the average Karachiite would have to nurture approximately 54 Banyan trees in their lifetime to offset their respective carbon footprints.

How did we Calculate this?

1.04 tons CO2 (prod. by the avg. national)

x 67.43 years (avg. life expectancy)

————————————————————–

70.1272 (avg. carbon footprint over lifetime)

÷ 1.3 tons CO2 (offset by the avg. Banyan tree)

—————————————————————

53.944 (avg. # Banyan trees necessary to offset carbon footprint)

≈ 54 Banyan Trees (trees can only be planted in whole numbers!)

Part 4: A Seed of Hope

In spite of steadfast campaigns launched by green activists, much ambiguity remains in the distinction made by local authorities between architectural and natural conservation. One must remember the respective significance of each to the broader social environment remains distinctive in its own right; natural landscapes bear just as much relevance in weaving the social fabric of society as do historic buildings. Just as the shattered stained-glass panes, the peeling plaster, and the iron-stripped balconies along the PCCC’s weekly Heritage Walks led by Shaheen Nauman bear testament to the previous grandeur of Karachi, the remaining Banyan Trees in Old Clifton are suggestive of a unique and enduring natural beauty – one that transcends beyond both colonial and modern times through the years of life reflected in their profusions of rings.

5 of the 68 Trees Designated as “Protected Heritage”

If Karachi’s built environment is recognized as “heritage,” why is it that natural landscapes are not part of the national maintenance system?

The Banyan Tree Project acknowledges green heritage as “protected heritage” and strives to render its “heritage” documentation a national exercise.

Part 5: The Path to Preservation

Since Pakistan’s inception in 1947, its rich cultural history has been marked by rare instances of successful legislation targeted at the prohibition of cutting trees, though the scope of this legislation has always been limited at best. Despite the passing of bills such as the 1927 Forestry Act focused on the ‘reservation’ of Sindh’s sparse mangroves or the subsequent ‘Cutting of Trees (Prohibition) Act’ of 1992, less than 0.74% of Pakistan’s land area today is marked by tree coverage.

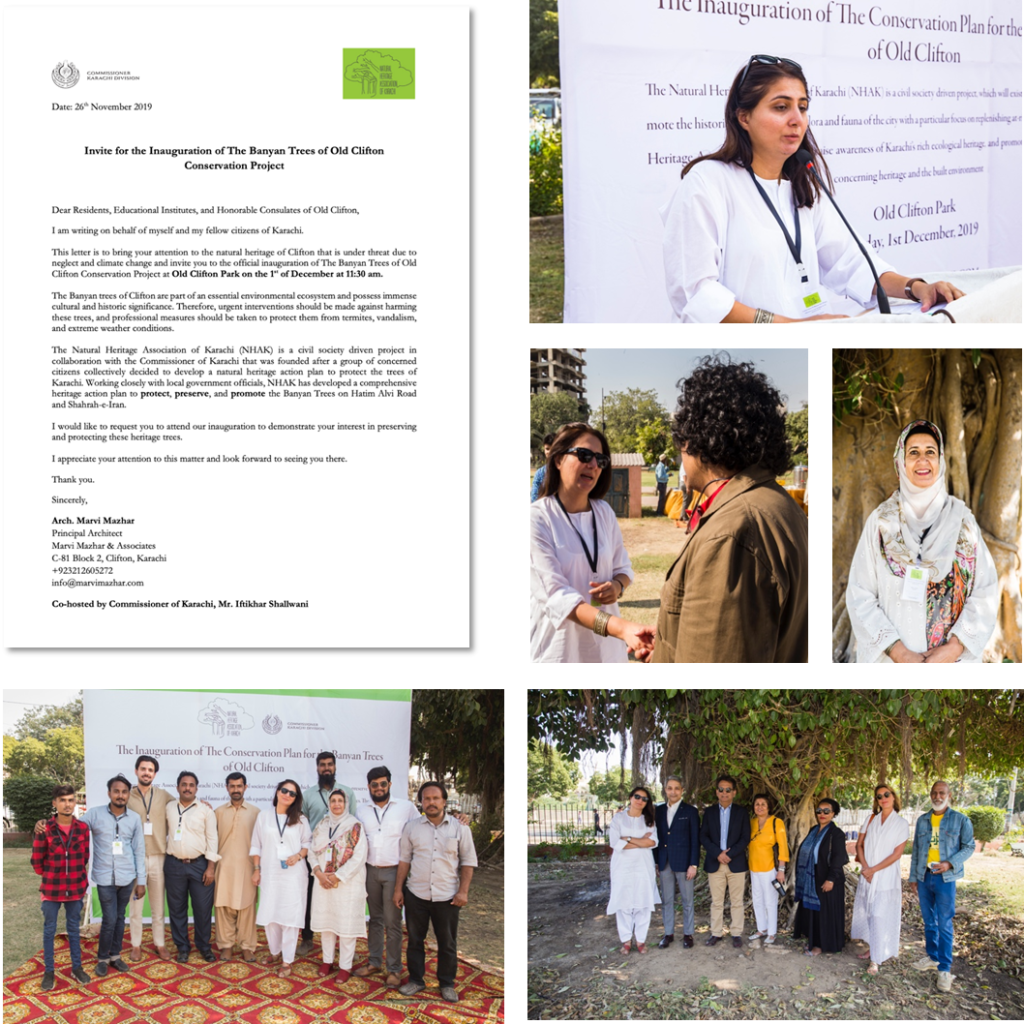

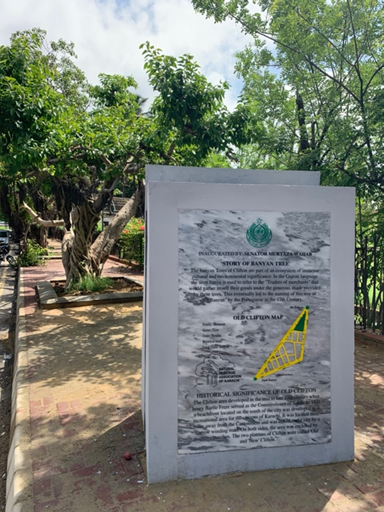

The Banyan Tree Project was initiated in 2015 after the demolition of unofficial heritage Banyan Trees to pave the way for the development of the Old Clifton underpass. Following the subsequent removal of several Banyan Trees across Karachi’s Shahrah-e-Iran road in September 2019, Architect and Activist Marvi Mazhar assembled a committee of concerned citizens comprised of Senator and Adviser to CM Sindh Murtaza Wahab, Environmental Activist Tofiq Pasha Mooraj, Film Director Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy, FM91 CEO Sara Tahir Khan, and Architects Arif Bilgaumi, Shahid Khan, and Mariyam Iftikhar. Together, they campaigned tirelessly to preserve Old Clifton’s sacred, centuries-old Banyan trees – the so-called ‘grandparents’ of Old Clifton, as fondly called by conservationists.

While the cause gained traction, they had yet to garner the support of the broader public. An invitation extended to Mazhar by the Lyceum school served as the first instance of an institution with its own Banyan population interested in the protection of surrounding Banyan Trees. Her September 28, 2019 address regarding their plight concurrently served to illuminate the student body on the gravity of the Banyan rehabilitation project and assured the protection of the Lyceum’s Banyan trees.

The event successfully sparked discourse among the youth, leading young author Qurutulain Choudry to author “Anmol Darakht,” an interactive book for children.

Mazhar, along with lawyer Umed Ali and former PCCC and MMA intern Uzayr Agha, published an article in Samaa on October 14, 2019, chronicling the past and possible future of the Banyan Trees of Old Clifton. They highlighted the unfortunate reality that Banyan Trees in Karachi are often felled for the paltry sums brought in by their extensive branches.

They further described how the grandeur of Banyans is merely a mask that has invited neglect in recent years – In contrast to what many may believe, Banyan Trees require extensive care, and even the “tiniest of termites” threaten to plague them.

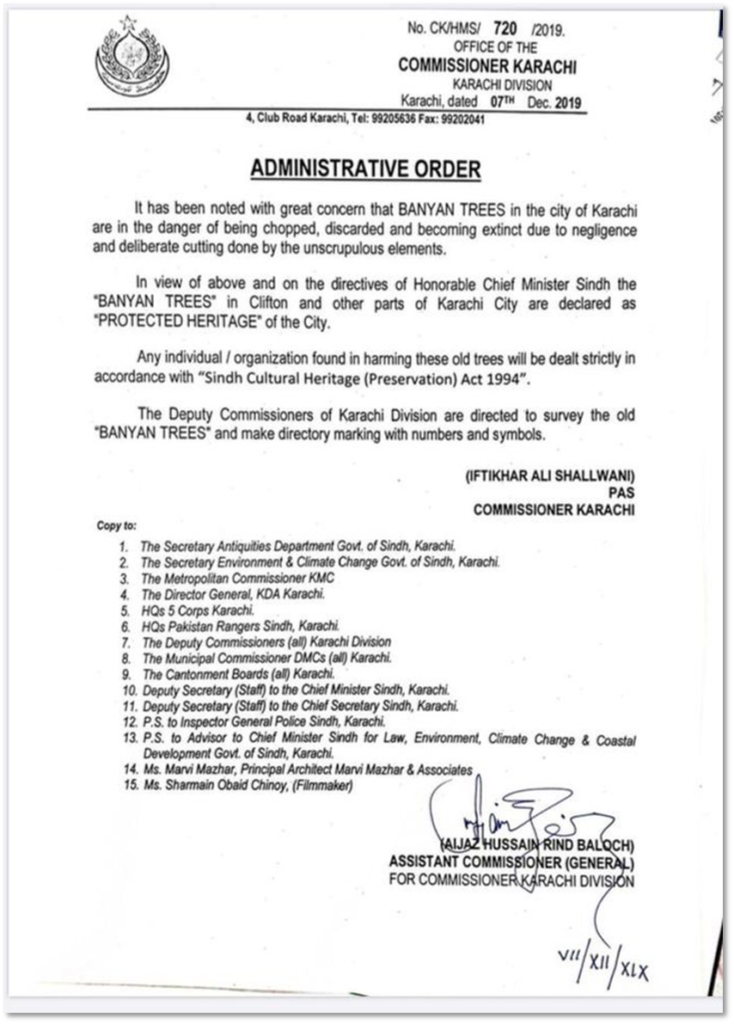

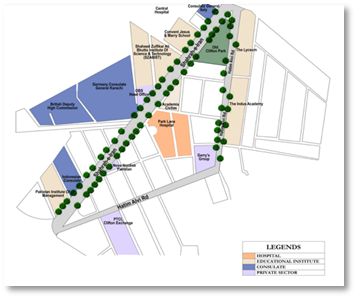

Following a month of unwavering effort to garner the attention of government officials, Mazhar secured an official meeting at the office of Karachi Commissioner Iftikhar Ali Shallwani on November 14, 2019. With former intern Uzayr Agha and prominent architect Shahid Khan in attendance, Mazhar pitched the preservation of Old Clifton’s ‘heritage’ Banyans. They promptly secured administrative authorization to proceed with architect Mohammed Mithai’s mapping of the 68 Banyan trees along Shahrah-e-Iran and Hatim Alvi Road leading to Karachi’s Old Clifton Park.

After recognizing the success of their activism, the concerned citizens who first shed light on the Banyan Tree Project formally organized their efforts to form the National Heritage Association of Karachi (NHAK), a crucial step in the fight for green-activism. This formal organization was symbolised by a logo designed by Kiran Ahmad in the subsequent weeks of November 2019.

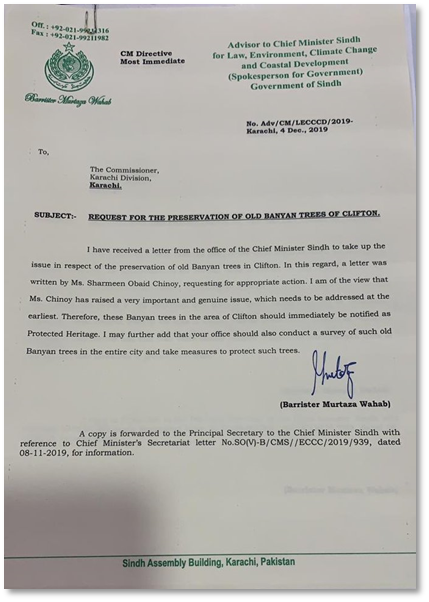

In celebration of the inauguration of the Banyan Tree Project on December 1, 2019, with consulate representatives and high-profile school, university, and upscale hospital administrative officials in attendance, Mazhar drafted a letter sent through Barrister Murtaza Wahab to the Karachi Commissioner on December 4, 2019.

The inauguration of the Banyan Tree Project not only brought civil society members together, but also solidified conservation efforts through the honorary appointment of Karachi Commissioner Iftikhar Shallwani as chair of the project.

Less than a week later, on December 7, 2019, the Karachi Commissioner approved the motion to declare the 68 Banyan Trees along Old Clifton’s Shahrah-e-Iran and Hatim Alvi Roads as “protected heritage” with an official administrative order.

The Banyan Tree Project, though initially established to preserve Old Clifton’s green-heritage, transcends a single focal point. With a significant number of Banyan trees located on pavements along the consulate-concentrated Shahrah-e-Iran road, the Banyan Trees have come to symbolize a place of convergence and congregation in a city “so deprived of non-gated public space” (Marvi Mazhar, Samaa Article) In order to deter loitering by those seeking shade under the canopies of the nearby Banyan Trees, consulates began the process of felling. With the support of the Deputy Commissioner South, Irshad Ali Sodhar, Mazhar countered the felling by placing terrazzo benches under the trees beginning in February 2020. The benches, designed by Architect Arif Bilgaumi, established the spaces around the trees as focal congregation points, encouraging discourse and the appreciation of natural beauty. Mazhar successfully conveyed the importance of spatial advocacy by strategically placing the benches facing towards the swaying branches of peripheral Banyans. The minimalistic design of the terrazzo benches reflects the fragility of day-to-day life in contemporary society. While wood can be stolen and resold, terrazzo offers a medium that can be optimized for comfort and aerodynamic purposes. Each terrazzo bench features a plaque, including the sprawling, aptly named “Rebel Tree,” dedicated as a touching tribute to late activist Sabeen Mahmud.

The beautification of the Banyan Tree sites encourages passers-by to pause in the midst of their day-to-day activities to make time for the serenity of the Banyan landscape. With a nod to her work for spatial advocacy, Mazhar ascertained that no space was left neglected. Conceptualizing and overseeing the rehabilitation of footpaths, Mazhar assured that minimalistic structures were erected to accommodate edges for the Banyan trees as opposed to former concrete-choking pavements that restricted the growth of their roots. The final product is a welcome diversion from other footpaths in the city characterized by encroachment and contestation. Stretching 8 feet in width and emphasizing the perfect balance of decorative accents, the footpaths fulfil Mazhar’s vision of an elevated pedestrian walkway.

In completing its first endeavour, the Banyan Tree Project marked a pivotal step in preserving the shared nature of public spaces that have been diminished by unofficial gated communities.

Unable to anchor its roots in the wet soil amid the 2020 monsoon season, a Banyan Tree was uprooted outside the Sindh High Court. Despite initial instruction for the tree to be cut, Mazhar and lawyer Alizeh Bashir advocated to save the Banyan.

Through the temporary insertion of pillars in the tree’s periphery to provide support, the tree is now growing once more and sprouting new leaves. We hope this success will inspire citizens to recognize that trees with weak root systems still have the capacity to flourish – with a little extra support, they can be given a new lease of life.

Part 6: An Idea takes Root

The Banyan Tree Project aims to promote a more sustainable way of life. While those overseeing the plantation are driven to take agroforestry approaches, individual users are encouraged to monitor and subsequently offset their respective carbon emissions.

The operation of the Banyan Tree Project relies on the association of each Banyan tree with users who have demonstrated interest in its plantation/restoration, enabling interaction between users and their respective Banyan trees. Each Banyan tree is listed under a distinct online page, under which it is photographed and geo-localized using modern GIS imaging. Designated municipal workers tend to the Banyan trees long-term health and ensure that plantations are conducted with respect to local biodiversity.

Part 7: Growing Greener

Relaunching the Banyan Tree Project with a digital focus, I intend to use modern GIS imaging, a means of assigning latitudinal/longitudinal coordinates to photos, to extend Banyan Tree preservation to plantation. Using GIS programming, project leaders can further designate plantation areas outlined by specific coordinates to assure plantations are carried out in accordance with agroforestry demands. Through enabling the easy navigation of green media on local maps, I plan to implement modern geotagging technology to locate Banyan trees, assure optimal quality control, and facilitate connection to users.

Through collaboration with green activists to increase awareness and scheduling youth outreach programs to deliver sustainability talks and distribute green curriculums, the Banyan Tree Project aspires to promote sustained environmental discourse that illuminates Banyan preservation as a long-term perspective.

Conclusion:

In spite of the rapidly industrializing world around us, where traces of the past often dwindle into forgotten history, Banyan Trees serve as a continuing connection to our pasts. Industrial development continues to proliferate at the expense of hundreds of Banyans that are left to wither and die. Breaking barriers and sparking discourse among a new generation of thinkers, the Banyan Tree Project demonstrates that there is no boundary that cannot be crossed if one is brave enough to take the first step. Take the first step and be a catalyst for positive change with the Banyan Tree Project and plant the ‘right green’ for Pakistan in the ‘right’ places for the ‘right’ purposes.

References and Other Links:

Newspapers/Blogs:

Arab News:

Samaa News:

ARY News:

MM News:

The News:

Urdu Point:

PakObserver:

Aurora:

OyeYeah:

Podcast(s):

The Localist Pakistan Podcast (Taking Ownership of Our Cities and Getting Things Done)

Youtube Video(s):

The Banyan Trees of Old Clifton (uploaded by Javaid Ahmed Solangi)